Victorian Silverplate Claret Jug

Victorian Silverplate Claret Jug

$425.00

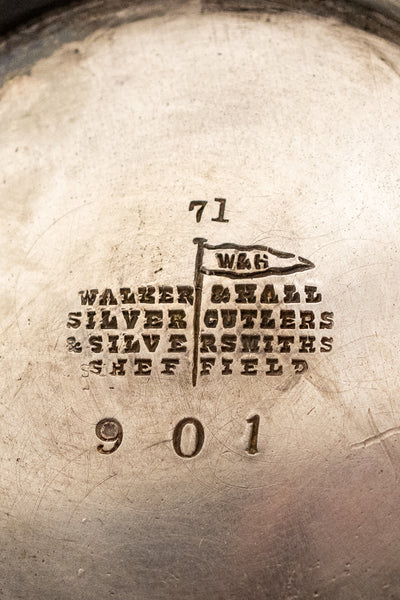

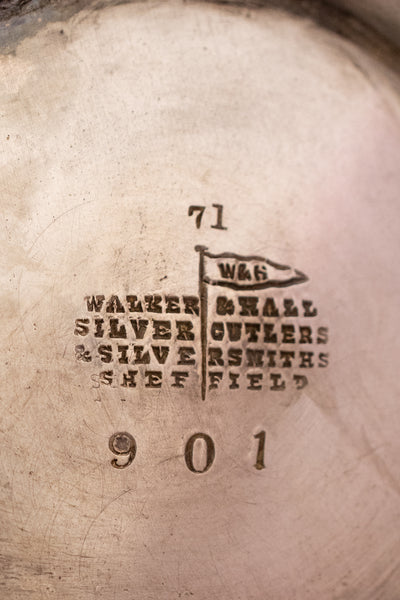

Sparkling over every detail of its surface, we are pleased to present this magnificent Antique Silverplate Claret Jug in all its stately glory. Gracefully imagined and elegantly designed, this special pitcher was found at a silver market in the north of England. Produced by the esteemed makers at Walker & Hall, the absence of a date stamp suggests this lovely claret jug was made prior to 1885.

First appearing in the 17th century as vessels for serving water—either drinking water or water for finger washing—these jugs (also known as ewers) began to be used for serving wine toward the end of the 18th century. Both functional and decorative, this exquisite pitcher features finely detailed fern and leaf ornamentation. It boasts a pleasing silhouette, with a dramatic curved spout and hinged lid, while a lavishly executed handle is cleverly juxtaposed against the sweeping curve of the jug’s sides.

A staple on the tables of wealthy Victorians, ewers allowed ample space for uncorked wine to breathe while helping preserve its taste and quality from the time of decanting until it was served at table by an attendant. Whether serving wine, water, or another beverage for yourself or your guests, this statuesque Silverplate Claret Jug promises to be a majestic addition to your sideboard, tablescape, or bar.

Strictly one-of-a-kind and subject to prior sale. In very good antique condition. 13"H x 5.75"D.

Learn More About Pteridomania

A great Victorian craze, pteridomania (from the Latin pterido, meaning ferns) was Britain’s passionate love affair with ferns and all things fern-like between the 1840s and 1890s. The term pteridomania was coined in 1855 by Charles Kingsley, author of The Water-Babies, in his book Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore.

The Victorian era was the heyday of the amateur naturalist. While pteridomania is generally considered a British eccentricity, fern madness invaded all aspects of Victorian life. Ferns and fern motifs appeared everywhere—in homes, gardens, art, and literature. Their images adorned rugs, tea sets, chamber pots, garden benches—even custard cream biscuits.

Originally marketed in the 1830s as plants that appealed only to “intelligent people,” ferns soon became a nationwide phenomenon. To collect ferns—the more exotic, the better—you needed a fernery, often a glasshouse where the ferns could be cultivated and displayed.